“Seven long strides shalt thou take: and if Long Compton thou shalt see, King of England thou shalt be.” - the Rollright Stones, Oxfordshire

Neolithic monuments on the threshold between two counties; woven into local yarns about witches, and stones going to drink from streams

Bonus issue! I’ve found myself with (unexpectedly) more time this week, so this is an extra edition before the usual one next Friday. Enjoy!

For ages, I’ve wanted to visit the Rollrights. I grew up on the edge of north Warwickshire, far from the county’s south border; marked by a spine of hills, threaded with historical landmarks such as the strange windmill at Chesterton, the Civil War battlefield at Edge Hill -- and the Rollright Stones.

The ‘King’s Men’, or the Rollright Stones.

Sometimes, as a teenager, on bike trips we’d venture as far south as Shipston-on-Stour, at the edge of the Cotswolds: somewhere that was a real, recognised place; a place that was featured on postcards, where people went on holiday. I remember how the fields seemed to grow mellower in the May sun as we rolled southwards, to spend the night atop the escarpment under a carapace of stars. In the secret woods and streaming gullets closer to our homes, we felt in more benighted and anonymous country: the sort that people didn’t visit unless it was for Stratford or Shakespeare. The sort where, when I arrived at university, you said you were ‘from Birmingham’ because that felt like the centre of the world.

From the top of the ridge by the King Stone; the view north towards Shipston-on-Stour and the rest of Warwickshire.

It was only later that I came to fully appreciate my home county: which had featured in my teenage poetry as I discovered the wonder of fields beyond the cul-de-sac’ed estates; the fact that, on study leave for GCSEs, I could cycle and lie in the grass beneath an oak avenue leading to an Elizabethan house; along the green lanes burgeoning with early summer scent through tiny villages with quaint names: Upper and Lower Slaughter, Hamptons Lucy and Magna.

It must have been in my second year at university when I started to investigate the question of whether there had ever really been a Forest of Arden: rummaged through boxes of secondhand books outside shops in Stratford for obscure texts on local myths and history. So it was that I came to learn of the Rollright Stones and the other strange landmarks at the south end of the county. To this day I have still only seen the Chesterton windmill from the Chiltern Line train, or the M40.

The Rollright Stones.

So when I discovered a friend was in lockdown very close to the Stones we agreed to meet for a socially-distanced walk. It was a sweaty climb up the short steep hill to the Whispering Knights: the remains of a ‘portal dolmen’, a type of Neolithic stone tomb dating from around 3500BC. A portal to another world. This was built around 1000 years before the actual stone circle, which is just one of a complex of monuments scattered atop the ridge: the limestone blocks gathered from the hilltop around. The Knights are impressive tapering limestones that lean on each other, exactly like soldiers huddling in to conspire. The capstone of the tomb has collapsed; just a fragment of human left cheekbone was found inside.

Approaching the Whispering Knights tomb.

A little further along the ridge, along what may have been the prehistoric trackway leading to the stones, we arrive to find a character sitting outside his campervan, with stickers advertising spiritual healing. He appears to be charging an entry fee, but when someone asks what it’s for, he says only, “beer.”

The Whispering Knights.

You can see why the site attracts spiritual types. Compared to the awesome megaliths at Avebury and Stonehenge the stones feel almost intimate: little figures huddling in a perfect circle, as if for some ritual; focusing intently, the view of the valley stretching below. Also known as the King’s Men, legend has it that -- similar to the nearby Knights -- the stones are soldiers turned into stone by a witch after plotting treason.

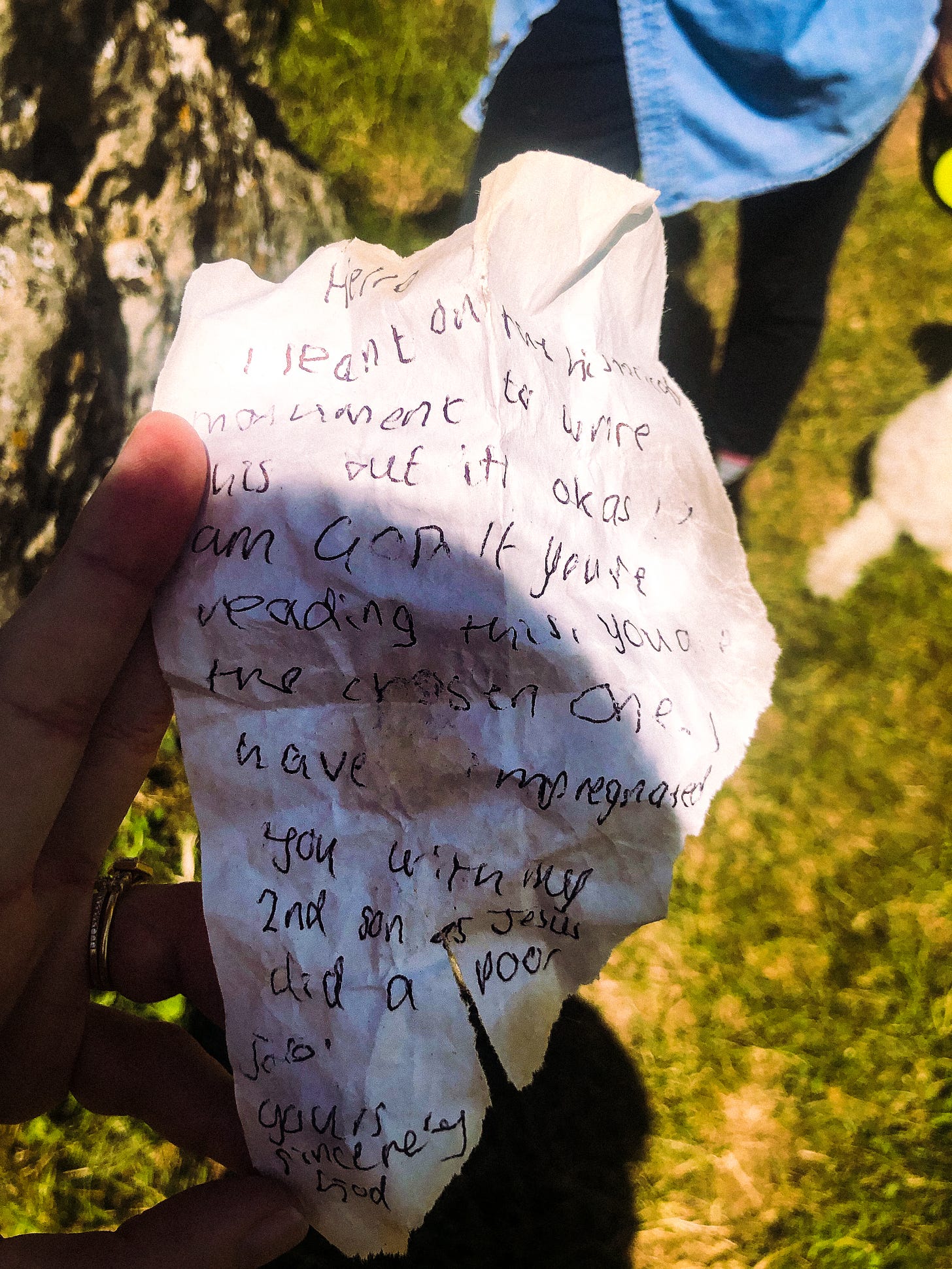

Originally there would have been enough stones that they were back-to-back, without gaps: the witches also, apparently, prevented anyone from being able to count them correctly. They come up only to about waist height, and are almost anthropomorphic: pocked, the 18th century antiquary William Stukeley described them as “corroded like worm-eaten wood, by the harsh jaws of time.” In some places you can pass your hand right through. In one such hollow we find a curious note: “Yours Sincerely, God.”

Curious note found in one of the hollows in the stone.

Myths surrounding the stones relate how they go down the villages nearby, and in particular towards bodies of water. The signboard at the site says that the Whispering Knights go down to drink from the stream at Long Compton on New Year’s Day. The King’s Men are also said to go down to the well at Little Rollright. Aubrey Burl, in his guide to stone circles of Britain and Ireland, states that a miller from the village dragged a stone from the circle down to dam a stream for his waterwheel, but every night the water drained away. After he found that the stone that had taken three horses to drag it down the hill took only one horse to return it, he chalked the mischief up to malicious witches in the village. A third story, from Andy Burnham’s book The Old Stones, states that the miller attempted to use the capstone from the Whispering Knights tomb to dam his stream, but it kept on every night returning to its original location. There are also tales of the King’s Men linking hands and dancing at midnight. Stukeley even claims that, “the country people, for some miles round, are very fond of [these stories], and take it very ill if anyone doubts of it, nay, they are in danger of being stoned for their unbelief.”

The King Stone.

Crossing the busy road, we reach the outlying King Stone: a majestic megalith on the slope of a bulge. Behind, the ridge drops into a long view: to Shipston on Stour to the north and beyond. The stone is now ‘S’ shaped, apparently from Welsh drovers who would chip off bits of it to make amulets. Here, witches are also supposed to have had a role. A king met a witch who challenged him: “Seven long strides shalt thou take: and if Long Compton thou shalt see, King of England thou shalt be.”

So went the king, gamely shouting, “Stick, Stock, stone. As King of England I shall be known.” The witch unsportingly caused a mound to rise up before him on the seventh stride, obscuring the village from view, cackling: “As Long Compton thou canst not see, King of England thou shalt not be. Rise up stick and stand still stone, for King of England thou shalt be none. Thou and thy men hoar stones shall be and I myself an eldern tree.”

Several tombs sit nearby: a round cairn just adjacent to the stone and a small round barrow containing an infant grave, both of which date from about 1800BC or Early Bronze Age. This places them about a thousand years later than the main stone circle. The King stone may have been erected later to mark the site of the burials; or, it may have originally served as an outlying stone to guide travellers to the main circle, and become a focal point for burials later.

Relaxing by the King Stone; Midge the dog seeking shade!

We sit on the brow of the ridge, virtually on top of where the round barrow is marked. There are a few large stones scattered around that people are using as benches; it is difficult to tell whether they are ancient or not. We crack open our beers and lounge on the grass, enjoying the sun and the long view down to Long Compton, town of witches, and Shipston-on-Stour beyond: apparently following an ancient tradition, as documented by Stukeley:

“Hither, on a certain day of the year, the young men and maidens customarily meet, and make merry with cakes and ale. And this seems to be the remain of the very ancient festival here celebrated in memory of the interred, for whom the long barrow and temple were made.”

— William Stukeley, Abury: a Temple of the British Druids

As we are leaving, passing by the main stone circle again on the road, we hear music through the hedge: a scraggle-haired man plucking folksy tunes on his guitar. It’s strangely atmospheric.

Cultural titbits I’ve been enjoying this week —

Fiction: the Woman in White, Wilkie Collins. A classic, I’m well aware, but I’m guilty of having totally overlooking Collins’s work till now. It’s a ripping yarn, taking in spooky country houses, disgruntled Baronets and mysterious wispy women escaped from Asylums. True Victoriana.

“We go to Nature for comfort in trouble and sympathy in joy, only in books… Our capacity of appreciating the beauties of the earth we live on is, in truth, one of the civilised accomplishments which we all learn as an Art… What space do they ever occupy in the thousand little narratives of personal experience which pass every day by word of mouth from one of us to the other? All that our minds can compass, all that our hearts can learn, can be accomplished with equal certainty, equal profit, and equal satisfaction to ourselves, in the poorest as in the richest prospect that the face of the earth can show.”

— The Woman in White, Wilkie Collins

Can’t say I agree entirely, but well put.

Film: The Madness of King George. An Academy-Award winner from the nineties from Alan Bennett and Nicholas Hytner. It’s strangely moving to watch the ‘the Tyrant King George’ (as we all know him from Hamilton) on his journey through little-understood ‘madness’, back to health and reigning his kingdom. He has a beautiful, elegiac speech on the America he lost:

“Forests, old as the world itself; meadows, plains; strange, delicate flowers. Immense solitudes. And all nature new to art: all ours, mine. Gone. A paradise, lost.”

Thanks and I hope you enjoyed this extra edition!

Please send me your comments, thoughts, feedback and recommendations! You can reach me on Twitter or Instagram and I’d love to hear from you.

If you enjoyed reading, please consider subscribing, or sharing this newsletter with a friend.

Sincerely,

Ruth

For much of the history and background in this article I am indebted to the following sources:

Aubrey Burl’s The Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland, and Brittany

Andy Burnham’s The Old Stones: A Field Guide to the Megalithic Sites of Britain and Ireland

William Stukeley’s Abury: a Temple of the British Druids, which features a chapter on ‘Rowldrich’ (or Rollright)

Strikes me as the perfect place for your blog.