Empty places and the endless present

The City of London: vacant stage of our former lives. Shades emerging to walk Liverpool Street station. The pandemic's unbroken flow of time.

I normally explore the weird and wonderful in the English landscape and write about it every couple of weeks. At the moment I’m confined to discovering the delight in my immediate surroundings. If this sounds like something that would interest you, why not subscribe? Or, if you’re already subscribed, consider recommending to a friend to whom it might also bring joy?

A friend was telling me about how she walked from her home in East London to Liverpool Street and it was strange to see such big places so empty, so normally full with crowds of people. We reminisced about the things we didn’t miss about our old lives. Among them, rushing across London on the Tube from place to place, spending money on Pret sandwiches, with a sense of impending dread — the constant feeling of being late for something.

I took a similar walk in November with another friend through the City. I have also thought it makes these places look somehow flimsy, as if they were a film set: normally a backdrop to the exciting play of life, but now the performance has stopped and it has been revealed for the artifice it is. In former times I have been comforted by the thought of thousands of people, every day, waking up, teeming through stations, toiling away in lights-on offices: a cast-iron certainty barring a nuclear strike. The reassuring sense of perspective; the swarm of human activity, of Life Goes On.

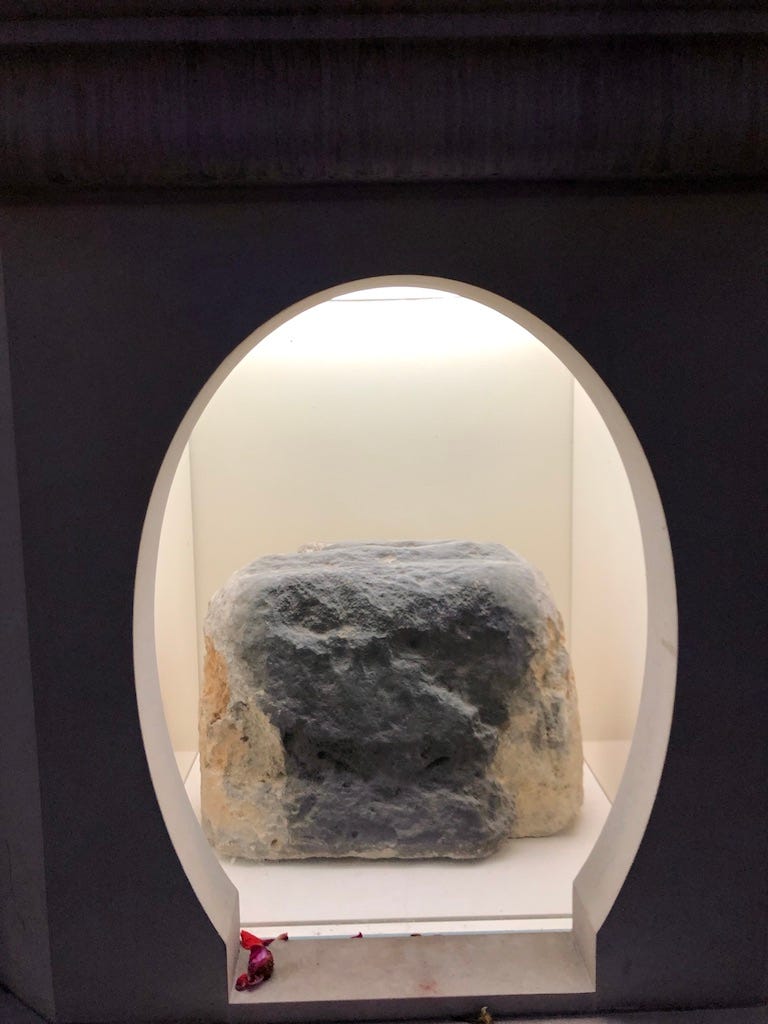

But now — the photos aren’t great because it was dark, and we were walking. But mostly there were acres of emptiness, cavernous shopping centres: like the ruins of some lost civilisation; where history was suddenly on an equal footing with the now.

WG Sebald talks about the old Liverpool Street in similar terms, as if it were some sort of magical portal; when there were still shady corners where you might be alone:

I suddenly found myself…at the entrance to the Ladies’ Waiting-Room, the existence of which, in this remote part of the station, had been quite unknown to me… I felt, said Austerlitz, like an actor who, upon making his entrance, has completely and irrevocably forgotten not only the lines he knew by heart but the very part he has so often played. Minutes or even hours may have passed while I stood in that empty space beneath a ceiling which seemed to float at a vertiginous height, unable to move from the spot, with my face raised to the icy grey light, like moonshine, which came through the windows … Although this light, a profusion of dusty glitter, one might almost say, was very bright near the ceiling, as it sank lower it looked as if it were being absorbed by the walls and the deeper reaches of the room, as if it merely added to the gloom and were running down in black streaks, rather like rainwater running down the smooth trunks of beech trees…

This disused space is now a stage for shades; for Austerlitz to wander, not only into his own, but into some sort of fantastical landscape of collective memory:

I saw viaducts and footbridges crossing deep chasms thronged with tiny figures who looked to me, said Austerlitz, like prisoners in search of some way of escape from their dungeon…

An echo of this sentiment, via Eliot, in this Tom Holland tweet a couple of weeks ago:

I went a few times to Liverpool Street in the last couple of months, to a co-working space where my company rents desks. I was here once, years ago, on a Scout trip, aged fourteen, changing trains for Harwich, to cross the sea to Denmark, wheeling our bikes onto the ferry as the wind whipped at our hair. I still remember that excitement: that touch of the metropolis as we sat on the tables outside and ate McDonalds, buffeted on the concourse, in our shorts and summer clothes, by the swarming commuters amongst the redbrick.

Now, the filmset emptiness of the station and the street outside, the normally-full taxi rank in the thin November light was trumped by the ‘office’, at the top of a lift in a low-storeyed building opposite. Decked out like a BA airport lounge, I touched the plants to check that they were real. It looked as though it had been put together hastily, some pioneering enterprise to refurnish the interior deserts that had arisen in skyscrapers all around. There were filament lightbulbs and laminate wood furniture. I worked at a desk where behind me there was a Peloton bike on which I saw no-one ride. Out of the window, I could see a single, bright white light flashing on a regular interval on one of the empty floors of the skyscraper opposite. When I went again a month later it was still there, flashing.

The pandemic also empties our lives of the social furniture that indicates the passage of time. Among them birthdays, Christmases, weddings and funerals. With this dearth of punctuation days are liable to run into one another in a never ending stream. I was going to write this is what life must have been like before civilisation but of course that isn’t true. Even the earliest peoples, since time immemorial, have had ceremonies to mark passing of the seasons and the year. The midsummer and midwinter; sun and moon; the sowing and harvest. In Ecclesiastes:

To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven:

A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted;

A time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to break down, and a time to build up;

A time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance…— Ecclesiastes 3:1-4

So perhaps that is why this endless present feels so strange. It will end, of course.

I hope you enjoyed this week’s random musings and can excuse them in lieu of a normal adventure. Please get in touch with me to let me know what you thought.

Is there something else you’d like to see that might give a lift during lockdown? You can comment directly on this post, or reach me on Twitter or Instagram: I’d love to hear from you.

If you enjoyed reading, please consider subscribing, or sharing this newsletter with a friend.

Sincerely,

Ruth