A wilderness in the heart of London - Abney Park

Decades of neglect rewilded this Victorian cemetery in Hackney - burial place of proud abolitionists and nonconformists

I explore the weird and wonderful in the English landscape and write about it every couple of weeks. If this sounds like something that would interest you, why not subscribe? Or, if you’re already subscribed, consider recommending to a friend to whom it might also bring joy?

Life is hard for all of us right now, which is why it’s nice sometimes to be reminded of death, or something. No, that’s not really where I thought I was going with that sentence either; but then probably if you go to Abney Park you’re going somewhere other than you expected. In the middle of buzzing Hackney, a place now heaving with people — people with tinnies, families, feeding the goats in Clissold Park, people coming around offering you free juices — this is a strange place where you could easily get lost; one of those woods where you could walk past the lamppost and walk out in another century.

Past the vast Egyptian Revival columns that proclaim the entrance, next to a graffiti’ed public building and a sign informing that this belongs to Hackney council, there is a cobbled path into what appears to be a thick wood, ivy-grown and tree-tangled. And yet among the wood, nestling poetically, there are gravestones; unevenly spaced, some crooked or collapsing onto their neighbours; some small and unassuming, others vast: classically inspired, topped with with urns and obelisks, reminiscent of those Appian Way tombs from antiquarian drawings.

I’m here with my friend Nick, who’s recently become a trustee of the Abney Park Trust. He explains the place’s appeal:

“To me, the magic of this urban woodland lies mainly in its uniquely multi-layered character.”

“It’s a designated nature reserve, a tranquil public space and a fascinating historic location all rolled into one.”

A few weeks ago Nick shared with me this fascinating essay on why English cities have so much green space — compared to, say, their continental counterparts. Abney is part of a long tradition in English town planning which dates back to Anglo-Saxon monasteries.

We walk along the winding paths, picking out the names of people — lawyers and bankers, soldiers and priests — who lived in Hackney’s burgeoning suburb: as Nick reminds me, a middle-class place for clerks and low-ranking professionals. Lesser known than some of London’s other famous ‘Magnificent Seven’ cemeteries such as Highgate, burial place of big names, Abney became neglected after the company that owned it fell into liquidation into the 1970s. Since then, the cemetery has become overgrown, making it the extraordinary urban wilderness it is today. Now under the care of energetic and responsible people, there are great plans afoot to restore Abney whilst preserving its unique character.

And yet Abney does have its fair share of big names: it became popular with Nonconformists after the closure of Bunhill Fields in 1854. Opening in 1840, the site was formed from the estates of Fleetwood House and Abney House, the latter of which had been home to the great hymn-writer Isaac Watts. There is a giant memorial to him there today; he who authored such favourites as Joy to the World, O God Our Help in Ages Past, and When I Survey the Wondrous Cross.

Isaac Watts, the nonconformist hymn writer.

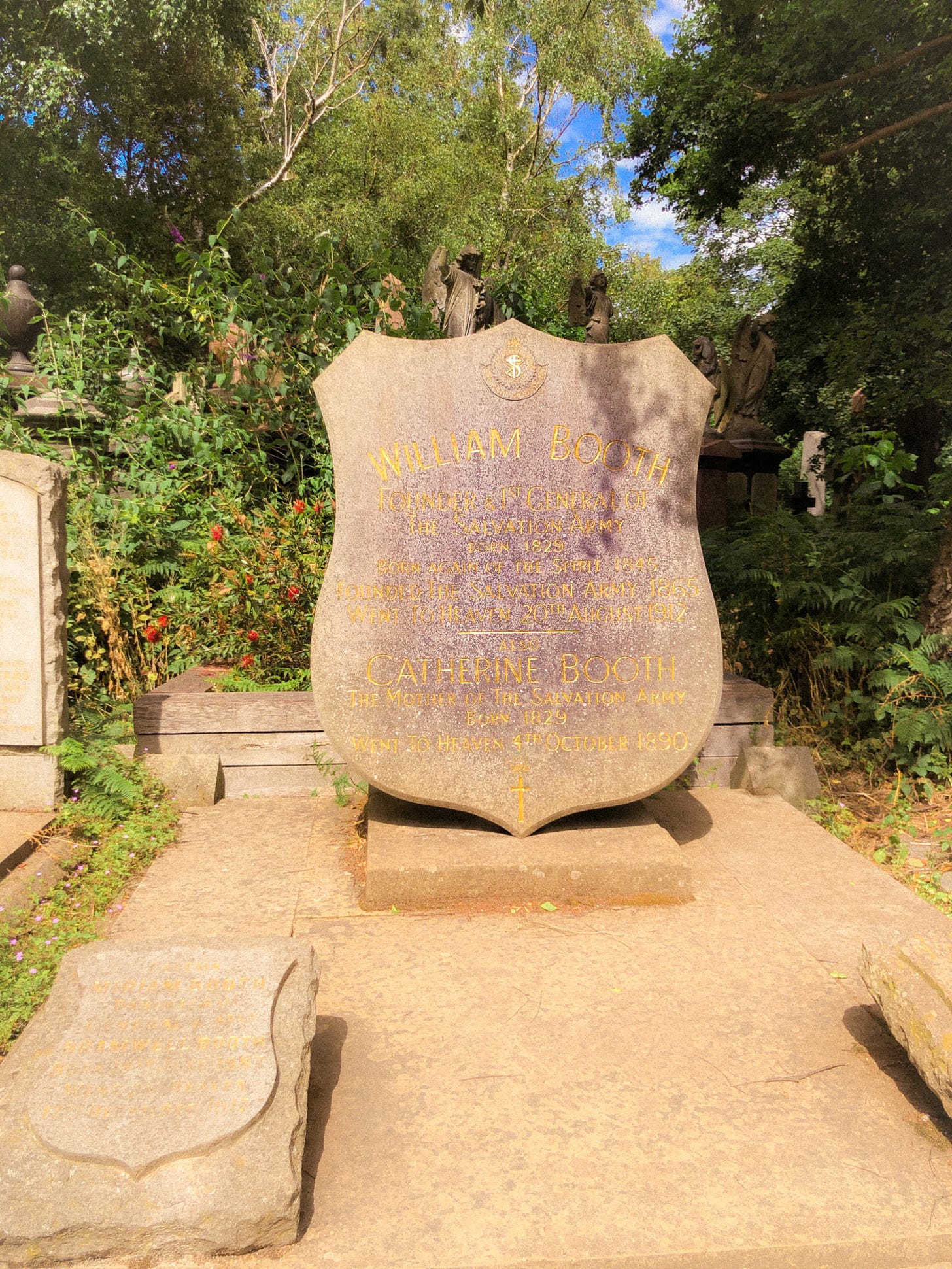

Not far from Sir Isaac are the graves of the Booth family; William and Catherine, the original founders of the Salvation Army, and their relatives and descendants. Looking as if they have been recently cleaned by present devotees, the gold lettering on the graves still sparkle in the afternoon sun.

The grave of William Booth, founder of the Salvation Army.

Other lesser known residents include Joanna Vassa, daughter of Olaudah Equiano (aka Gustavus Vassa) who was a freed slave and anti-slavery campaigner. She is not the only person with abolitionist connections to the site: many who were present at the Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1840 are buried at the site including Joseph Sturge, founder of the Anti-Slavery Society; Josiah Conder, who wrote poetry about the horrors of the slave passage; and Reverend Joseph Ketley, who was a minister to a slave congregation in what is now Guyana, among many other prominent nonconfirmists involved in the Abolition movement.

The chapel in the centre provides a visual example of Abney’s nonconformist values: the oldest surviving non-denominational chapel in Europe, its unique design combines different elements of sacred architecture to symbolise them all. The church’s cross-shaped layout gives equal size to the top three arms, as is customary in Greek Orthodox tradition. You can’t go inside now; it’s derelict, with a Lottery grant incoming for restoration. The outside is clouded London Yellow Stock brick; the gates across the former carriage entrance locked, and the Bath Stone dressings on the front chipping away.

The chapel at Abney Park.

In surely a great example of the Victorian frenzy for order, the cemetery was originally laid out as an arboretum, the trees planted from A to Z. Ironically this has set the seeds for the rich thicket it now is today, gravestones revealing themselves unevenly from the undergrowth, many more hidden in the vegetation where the strange winding paths don’t penetrate. In one way, I tell Nick, perhaps the reason it is so arresting is because it is like a vision of the future, one that we never see: this is how civilisation becomes ruined. When I was a child I would always see old buildings, like ruined castles, and wonder: how did they get like that? It couldn’t be purely a natural process, because there were buildings as old as that that weren’t ruined: people lived in them. And this is the key point: neglect isn’t natural, but cultural. It happens when there is no longer a reason to care for something: when the social structures that were in place to maintain it wither away.

Normally this happens when there is a discontinuity between one civilisation and the last: like when the Roman Empire left Britain, and we lived in the ruins of the stone buildings for centuries, unable to rebuild them on our own. A phenomenon lyrically conjured by the great Anglo-Saxon poet of ‘The Ruin’:

Wondrous is this stone-wall, wrecked by fate:

the city-buildings crumble, the works of the giants decay.

………………………. a hundred generations

have passed away since then. This wall, grey with lichen

and red of hue, outlives kingdom after kingdom,

withstands tempests; its tall gate succumbed.

— trans. Kevin Crossley-Holland, The Anglo-Saxon World: An Anthology

To this poet, the people who made these buildings — possibly those of Roman Bath — seemed so distant as to be of mythical proportions: ‘giants’.

It is almost inconceivable for us now to imagine the ruins of our present civilisation. To imagine when our way of life might dry up and people decide to stop caring for the things we now consider monuments. It’s this sense of obscurity that’s so arresting about a visit to Abney park: it’s like a vision of the future. We almost never see anything ruined — graves as recent as 150, 100, 50 years old — that feels so close, almost within living memory. These people probably still have living relatives. And so it’s a salutary reminder of what the ruins of our civilisation might look like. It reminds us that nothing lasts, at least not in the way we expect.

Short panorama near Isaac Watts’ statue at Abney Park, with birdsong.

Things I’ve been enjoying this week:

Film: Master and Commander, The Far Side of the World. I didn’t expect to enjoy a film about life aboard a Napoleonic-era British warship on the tail of a French man o’ war as much as I did. What made it so arresting was the level of detail with which ship life at that time was rendered: the eight-year-old officers, the kitchen-table surgery, the food, the cramped quarters, the sea-shanties, the discipline and ship’s prayers, the funeral rites, the captain and his friend practising string duets in the middle of the Pacific. Rarely have I been so immersed in a fictional world.

Theatre: Lungs, The Old Vic. You can still get tickets to this livestreamed run of Duncan Macmillan’s play from the empty auditorium at the Old Vic. The performance — about a highly-strung couple (Claire Foy and Matt Smith) trying and failing, to have a baby, and then a relationship, and then eventually (somewhat) succeeding at both — is socially distanced, and they’ve accommodated this with excellent use of streams from two simultaneous cameras. These operate like two windows which the characters move between, making them feel closer than they are. This was a different experience to watching real-live theatre (as my husband mentioned, “you can check your phone in the boring bits”), but no less moving for all that. Their neurotic and circular debates about the state of the planet feel timely and fitting, but they eventually find a way out of the labyrinth.

I’d love to hear your ideas for other historical walks or places to explore around London — big or small. Is there something in your neighbourhood that deserves more attention, perhaps?

Please send me your comments, thoughts, feedback and recommendations! You can comment directly on this post, or reach me on Twitter or Instagram: I’d love to hear from you.

If you enjoyed reading, please consider subscribing, or sharing this newsletter with a friend.

Sincerely,

Ruth

For this article I am indebted to:

Abney Park’s excellent website, well worth a visit for its wealth of information on this place and its heritage.

The Anglo-Saxon World: An Anthology, translated by Kevin-Crossley Holland, for the excerpt of ‘The Ruin’. (Also a fantastic read.)